A stoic, an epicurean, a cynic and a skeptic walk into a bar

Rob James

A guide to collecting and distinguishing these philosophies of austerity.

May 25, 2025

In True Detective season 1, Rust Cohle says that as a “philosophical pessimist,” he is not a lot of fun at parties. The same could be said of each of the four principal schools of Greek thought that emerged shortly after Aristotle.

Today’s Compensatory Culture post surveys stoicism, epicureanism, cynicism and skepticism and some applications to life. A special feature Attachment is what I believe to be the first separate transcription of the brilliant W.H.D. Rouse marginalia to the epicurean classic De Rerum Natura (On The Nature of Things, or The Way Things Are) by Lucretius. If you want to get to know that work, there is no easier and more faithful summary.

STOICISM

This school dates to the porch or “stoa” occupied by Zeno of Citium (334-262 bce) in Athens, a bit after Aristotle held sway in the Apollo-as-Wolf-God-Temple or “lyceum.” (Other location-names for traditions include the grove or “academe” for Plato and the garden for Epicurus.) He and his followers did have a theology of sorts (alternately God, nature, or “the gods”) and a cosmology, but later readings have focused on the ethics in the broadest sense, how should we live.

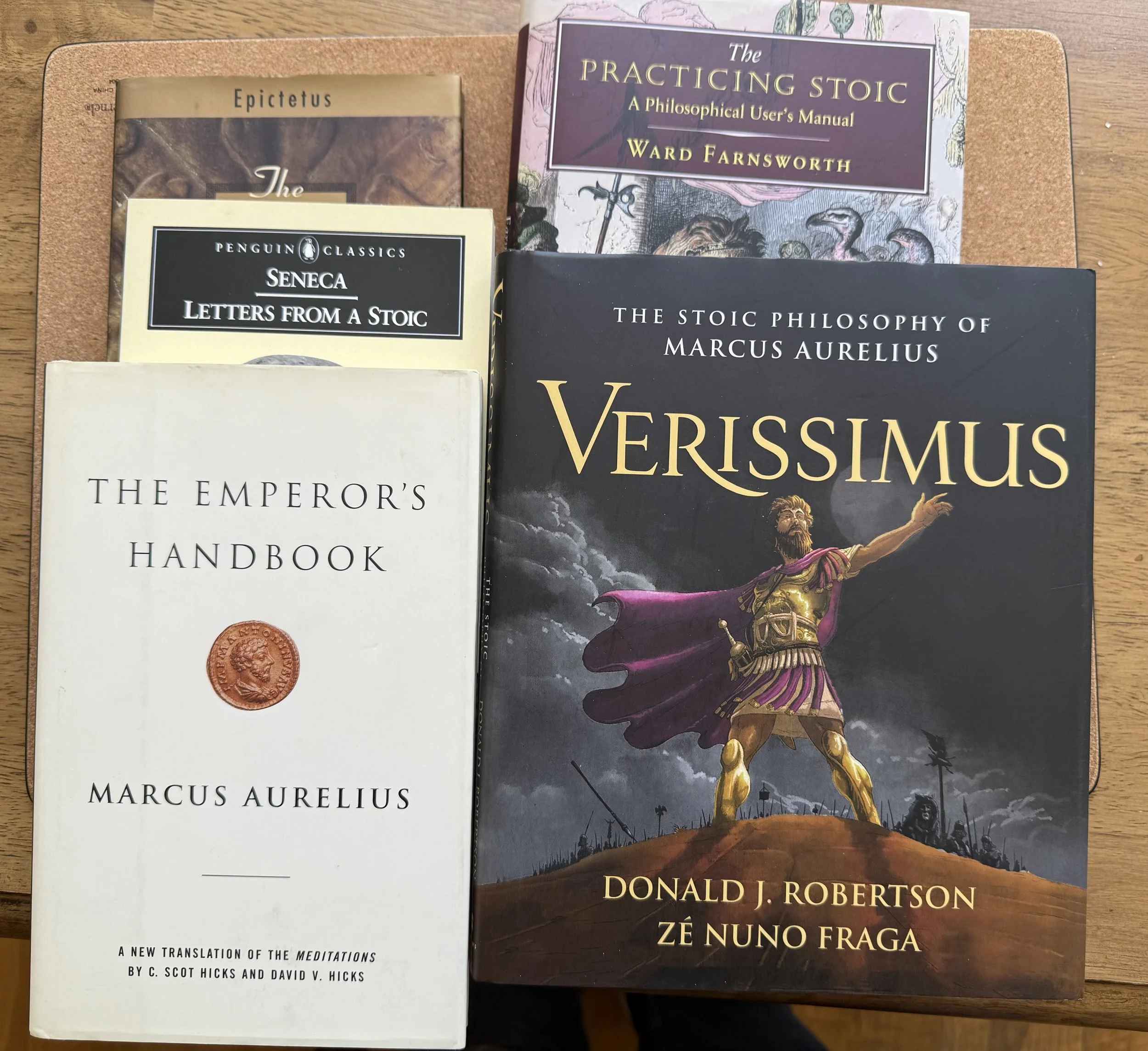

The main readings come to us through Seneca (4 bce-65 ce, rags to riches to suicide after falling out of favor with Nero) and his Letters; Epictetus (55-135 ce) and his work as transcribed by his student Arrian into the wonderfully named Diatribes (discourses) and Enchiridion (handbook); and the fifth of the Five Good Roman Emperors Marcus Aurelius (121-180) (MA) and his Meditations in Greek, mostly jotted during his endless Germanic campaigns. Authors like Cicero, Montaigne and Samuel Johnson selectively restated and refined their observations. Ward Farnsworth’s The Practicing Stoic (2018) is an attractive and well-organized compilation of the most commendable pieces, leaving behind the religion and astronomy and damping down some of the colder advice (his trying to contextualize Epictetus’s advice not to internally grieve over another person’s sorrow comes off as what a lawyer might call special pleading).

The key stoic concept is that virtue is the end of life, “let virtue lead the way.” When good or bad things happen, you react not to those things but to your opinions or judgments about them; “it’s up to you” (MA 1.17), you can change your opinions and judgments (a precursor to the Serenity Prayer). Live only in the present; live as if your next breath will be your last. Be indifferent to pleasure and to pain—you can be happy no matter what if you live in accordance with nature. Contrary to rumors, stoics are not robotic Mr. Spocks—they encourage friendships and fulfillment of citizenship obligations, just those based on character not “fair weather” friends and causes (don’t let your life depend on the opinions of others). A killer line from Seneca: Someone who becomes your friend because it pays will cease being your friend if it pays (I’ve experienced that one!). His take on gladiator battles: “men were strangled lest people be bored.” As with other Greek schools, they say “know thyself” and “nothing in excess.” “The measure of a man is the worth of the things he cares about” (MA 7.3).

The Meditations read like a modern self-help guide (Marcus Aurelius had stoic training called therapeia, “therapy”). “Someone wrongs me. Why should I care? That’s his business” (MA 5.25). If you ever start to feel angry about someone who has offended you, simply apply these easy “ten gifts from the Muses” (MA 11.18):

Put the offender in the context of all of mankind

Pity the offender, enslaved as he is by his own opinions, conceits, and arrogance

Excuse the offender for his ignorance; no one does wrong knowingly (cf. Socrates)

Remember that you offend sometimes too

Reflect that you can’t always be sure who is in the wrong

Recall that life is short and that we and the offender will die soon

Know you are angry at your own judgments not the actions of others, so remove those judgments

Realize your anger in response can cause more suffering than the original offense

Acknowledge that an offense may attack your body, but can’t touch your moral character unless you allow it to do so

Heed Apollo who tells us there are bad men who will do bad things; don’t expect the impossible, rather anticipate the possibility of bad men and bad things every morning.

All righty then. (I could never check off more than a handful of these when I’m angry.)

Living the stoic life is a tall order and even adepts must fall short. It is hard not to internalize “a decent respect to the opinions of mankind” (Declaration of Independence, authored by Thomas Jefferson who included stoic thought among his many contradictory natures).

EPICUREANISM

Obviously this school derives from Epicurus (341-270 bce), whom we know mainly from quotations by others. The great modern source is the improbable, a beautiful extended poem by the Roman Lucretius, The Way Things Are. Just as stoics are not unemotional Mr. Spocks, so epicureans are not luxury-loving sybarites. Both stoics and epicureans caution to avoid excessive pleasures and desires, stoics because virtue is the key, and epicureans because we should focus on avoiding unnecessary pain and seek only natural pleasures.

What are those pleasures? Natural and necessary are food, drink, sleep and shelter; natural and unnecessary are reasonable sex, children, and the esteem of others (here the stoics part company). Pursue those rather than the unnatural ones like too much alcohol and sex. The focus on pleasure means that virtue is instrumental, a means to an end rather than the stoics’ end in itself. Don’t violate the law, both schools say: the stoics because it’s unethical and the epicureans because of the pain from getting caught and punished.

Epicureans urge retreat from the world—“live hidden,” have a small number of close friends. Death means nothing, our atoms return to the universe and get remade into something else. “The most terrible evil, death, is nothing for us, since when we exist, death does not exist, and when death exists, we do not exist.” Don’t fear either death or the gods.

SPECIAL FEATURE ATTACHMENT: The Rouse Marginalia to The Way Things Are

Lucretius spins the epicurean approach into a wonderful extended work touching on all the liberal arts and sciences—cosmology, physics, biology and psychology. I leave all that to the linked Marginalia transcription, so please take a look.

CYNICISM

This school derives from Antisthenes, a student of Socrates, but reaches its apex with Diogenes of Sinope (and Crates a bit later). At root it is a pessimistic view of all of human nature—we all pursue self-interest rather than virtue. Distrust all authority. Truth is subjective. Live simply and live apart, reject any necessary participation in civil society. Their literary style is biting—satire, mockery. These folks are Eeyores, really bad at parties.

SKEPTICISM

Often confused with the cynics, the skeptics include Pyrrho of Elis and Sextus Empiricus. Pliny the Elder (“nature’s chief blessing, death”). But they are hesitant and reserved rather than pessimistic. They want evidence in the form of logical proof and factual justifications for statements and beliefs. They are inquisitive not negative, though if you go around suspending judgment forever on everything, the difference is hard to spot and they may come off as apathetic and passive. They hope that truth is objective, that it is “out there”—maybe more like Dr. Dana Scully than Fox Mulder.

###

There are times in my life when I feel like a stoic, an epicurean, a cynic and a skeptic. And there are other times when I mix them and still other times when I deviate from all of them. I hope this run-through of the differences helps me and others to organize the silverware tray of the cluttered kitchen of the mind.