George Eliot, marriage counselor?

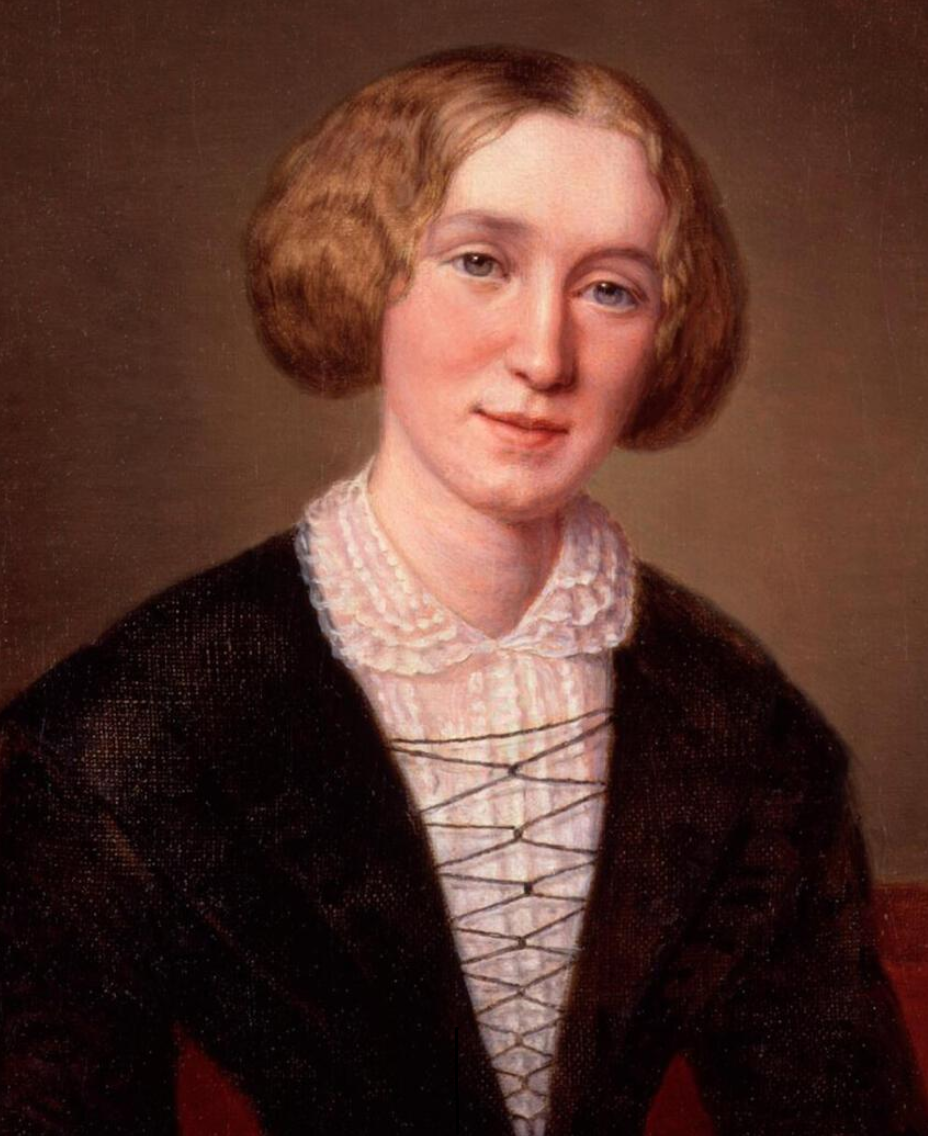

Mary Ann Evans defied in her life, but depicted in her work, social conventions and modes of belief.

Rob James

October 1, 2025

Were it not for her masterful sprawling Middlemarch, I doubt I would have taken this summer sojourn through the works of George Eliot, the pen name of Mary Ann Evans (1819-1880). I enjoyed that novel and its 1993 BBC adaptation more than the melodramatic Silas Marner (and I knew nothing of the others save a Monty Python sketch briefly name-dropping The Mill on the Floss). I later learned she translated the works of the skeptics David Friedrich Strauss, Ludwig Feuerbach, and Baruch Spinoza. That combination, plus her own amorous adventures (scandalous in Victorian England), made this survey (in the words of the Michelin restaurant guide) “merit the voyage.”

The Life

Mary Ann Evans was born into wealth but considered unattractive and therefore cruelly thought not “well-marriageable.” Her father plunged her into his library, where she quickly mastered ancient Greek and modern European languages. The family moved to a suburb of Coventry, eventually the model for the fictional Middlemarch. There she met Robert Owen and Herbert Spencer, and became acquainted with the works of the Young Hegelians Strauss, Feuerbach and Karl Marx.

In 1846, she translated Strauss‘s Life of Jesus, which likened the miracles of the Holy Gospels to fairy tales. The Earl of Shaftesbury memorably dubbed it “the most pestilential book ever vomited out of the jaws of Hell.” She soon translated Feuerbach’s Essence of Christianity (and Spinoza’s Ethics, not published until the 1980s). I have covered or will cover those three fellows elsewhere. Here I will record that Strauss (1808-1874) was a demythologizer (he professed belief in the divinity of Jesus but thought (like Thomas Jefferson and Leo Tolstoy) the miracles were invented by the early Church to tie Christ into lore about the Jewish Messiah); Feuerbach (1804-1872) was an atheist and materialist (holding that men projected their own imperfect state onto a perfect deity and a perfect afterlife); and Spinoza (1632-1677) was a pantheist (equating “God or Nature” (Deus sive Natura, Latin for “you say tomato, I say to-MAH-to”), critical of human religions and religious governments, and urging us to value life, liberty and love for their own virtues).

She met George Henry Lewes and lived with him from 1854 to 1878 while Lewes’s wife was herself living with someone else. All in all it was quite the Victorian disgrace, cured only in 1877 when George and “Mary Ann Lewes” were properly introduced to the daughter of the Queen. (Mom Victoria was a big Middlemarch fan and commissioned paintings of the scenes.) After Lewes’s death, she married John Walter Cross and more conventionally took his surname. She died shortly thereafter and was buried in Highgate among other dissenters and agnostics—like Marx and Spencer, a combination that sounds like a department store.

The Works

I was able to download on Kindle the complete works for ninety-nine cents. I skimmed some of the works while delving more deeply into the others. George Eliot writes elegantly if excursively, and I particularly enjoy the passages where her voice is that of a sardonic narrator. It is especially her examination of the human, all-too-human weaknesses exposed in the pursuit and course of personal relationships—I hesitate to call them “romances,” as nearly all of them turn out unilateral or mutual disasters or disappointments—that provokes me to dub her a “marriage counselor.” I mean that in a cautionary sense: learn from her many counter-examples!

Scenes of Clerical Life (1858). These three early stories (about Rev. Amos Barton, Vicar Grifil, and Janet Dempster) strike me as talky, period drawing-room pieces, revolving around a minister and his social circles, and some fine distinctions among Anglicans, Methodists, and other denominations. I did like the occasional line. For one, “The first condition of human goodness is something to love, the second something to reverence.” For another, a stinging remark on leaving the company of others is captured perfectly by her classical allusion to the departing Parthian horsemen, who fired arrows behind them and thus “wounded [their attackers] as they flew.”

Adam Bede (1859) is set in 1799 rural Hayslope and is full of the transcribed dialect (“d’ye” and its ilk) of which the nineteenth-century English novelists are fond. I expected to dislike this novel, but slowed down my Kindle page-turning to savor it.

The plot centers on what others call a “love rectangle” but I call a “love polygon”—starting with the stout noble carpenter Adam Bede, the ingenue Hetty Sorrel (“Hetty’s was a springtide beauty, it was a beauty of young frisking things… a false air of innocence”), the haughty aristocratic Captain Adam Dennithorne, and the fervent Methodist preacher Dinah Morris (hence a “Methody” and a dissenter from the Church of England; her open-air sermons give George Eliot an opportunity to convey her own dissenting religious views). I call it a “love polygon” because young women like Hetty are always avidly sought after by others, in her case Adam’s own brother Seth and other villagers.

This work is said to bear the influence of Thomas Carlyle, but I felt more resonance with Thomas Hardy’s later Far From the Madding Crowd with stout Gabriel Oak, dashing Sergeant Francis Troy, and my earliest crush Julie Christie as Bathsheba Everdene in the 1967 movie. I will not spoil the plot, but will say that a child’s death was considered despicable at the time. The ending is for me badly marred by a series of sudden personality turnabouts—Hetty, Dennithorne, Dinah each abruptly changes character. Everyone acts contrary to his or her prior conduct. Everyone except Adam, really.

The Mill on the Floss (1860). This is the story of the sensible realist Tom Tulliver and his wild idealist sister Maggie Tulliver, growing up around 1829 in the Dorlcote Mill on the river Floss near the town of St. Oggs (all fictions). Maggie kindly looks on the hunchback Phillip Wakem, the son of the lawyer who has ruined her father. Her cousin Lucy Deane was intended for the wellborn but unreliable Stephen Guest. After Tom forbids Maggie’s relation with Philip, she becomes something of an ascetic a la á Kempis. There is a series of improbable boating incidents, and Tom and Maggie reconcile as they meet their common end.

Silas Marner (1861). A novel about alienation. I first encountered it, believe it or not, as a Classics Illustrated comic book in the late 1960s. Nietzsche criticized the work for implying that suffering would lead to redemption, and I think he has a point.

Marner the physically plain (a George Eliot stand-in?) linen-weaver is exiled from his church for theft. He was likely framed, but nonetheless leaves for the village of Raveloe. There he becomes a hermit and a miser, hoarding his gold. It is robbed from him. A two-year-old orphan, left by her mother (involved with the robber) dying in the snow, wanders into his house. He gives her the name Hephzibah or Eppie and there are scenes that are rather treacly (“dad-dad”). Eventually, the thief returns the money. A message of the novel on one superficial level is that love is more important than money, I guess.

Romola (1863). A tale of late fifteenth-century Florence, in the time of Savonarola and the bonfire of the vanities. I skimmed this one even faster than the others.

Felix Holt, the Radical (1866). A tale of the 1832 Reform Act, which expanded the franchise and eliminated the rotten boroughs in favor of city representatives. There is another love polygon, this time an ordinary triangle among the dissembling political poseur Harold Transome, the earnest genuine refromer Felix Holt, and Esther Lyon.

Chronologically, I skip over Middlemarch and conclude the survey part of this piece with:

Daniel Deronda (1876), the only Eliot novel set in the then-present day, in both Germany and England. There is a complicated plot involving Daniel and Gwendolen Harleth. Daniel rescues a Jewish woman, Mirah, who introduces him to the London Jewish community and his own roots. Her brother Mordecai or Ezra espouses proto-Zionist views of returning to the Holy Land. His arguments may reflect some of George Eliot’s own views on the situation of Jews in Britain in particular and Europe in general.

The Classic

Now I go backwards to Middlemarch (1872), which with all due apologies I will cover in great detail. I am unashamed to commit many spoilers, because this is [ahem] A Great Work that Everyone Should Read. Before proceeding to this part of the post, kindly attack the book or at least watch the excellent BBC miniseries.

George Eliot’s view of marriage parallels the Duke of Wellington’s (apocryphal?) appraisal of the battle of Waterloo—namely, a good one is “a close-run thing.” Your choice can fatefully consign you and your mate to domestic bliss, to lifelong ennui and regret, or to abject misery.

The title combines “middle” (neither hot nor cold, urban nor rural) and “march” (a border or fringe region). The word “provincial” in the subtitle, “A Study of Provincial Life,” can be taken literally as a novel set in a town outside any great metropolis, or figuratively as connoting small-mindedness.

Dorothea Brooke is the ward of her uncle, the estate holder Arthur Brooke, who we are told will ultimately run for Parliament after the 1832 Reform Act. (Incidentally, the book was published not long after further reforms were enacted in 1867.)

Before that legislation, back in 1829, Dorothea is a pious and serious girl, devoted to improving the living conditions of the family’s tenants. She rebuffs a marriage proposal by the amiable and simple baronet Sir James Chettam, who is the kind of man who says “exactly” even after Dorothea says something that is ambiguous. He promptly turns his affections to Dorothea’s more conventional sister Celia.

Nope, Dorothea has inexplicably set her sights on an older scholar, Edmond Casaubon. He is writing a massive work titled The Key to All Mythologies. Dorothea fantasizes that she can be his helpmeet, together with him plumbing the mysteries of syncretism of Christianity with all other beliefs. They marry, to Arthur’s dismay, but she quickly learns that Casaubon has no intent of intellectual relations or indeed any relations with her, shooing her out of his study. The couple travels to the Continent, where Dorothea is miserable. Moreover, she discovers that Casaubon is a fraud: he doesn’t read German, in which all the best mythology research has been written for the last twenty years, and he has no theory to expound whatsoever.

Casaubon has an impecunious and “disinherited” nephew, Will Ladislaw, to whom he gives money. Will immediately falls in love with Dorothea, but the married woman is externally cool to his advances. It is an miserable house not a home.

Meanwhile, His Honor the mayor of Middlemarch, Mr. Vincy, has at least two children, Rosamond and Fred. Rosamond is a girl who likes the finer things in life and focuses on social climbing to get them. She sets her sights on Tertius Lydgate, who is of elevated birth but limited means; he is the idealistic physician who comes to town with new thoughts about medicine. He wants a hospital dedicated to modern principles. In this he is supported by Nicholas Bulstrode, a wealthy patron of the town and outwardly a man of rectitude. Tertius cooperates with Bulstrode in installing Tyke as hospital chaplain even over his own friend Camden Farebrother, who is thus turned out of a remunerated position. Bulstrode is married to Vincy’s sister Harriet, and Mrs. Vincy’s sister is the second wife of a wealthy man named Peter Featherstone. This town is very closely close-knit, it seems.

We first meet Fred Vincy as a wastrel who spends money profligately, comfortable in his expectation that he is the next surviving heir of … old man Featherstone. Featherstone’s only known other relation is his niece Mary Garth, a very sharp and ethical but plain girl (another likely stand-in for George Eliot herself). Mary’s father, Caleb Garth, is an easy touch for Fred, who asks Caleb to lend him money and to co-sign a loan to finance a harebrained horse-purchasing scheme. The scheme fails, of course, and both Fred and Caleb are wiped out—depriving Mary of even the small sum that Mrs. Garth had set aside for her benefit.

As it turns out, Featherstone has two wills; he asks Mary to destroy one of them, but Mary declines to play any part in such an act. In the authoritative will Featherstone has left his wealth not to Fred but instead to his hitherto unknown illegitimate son, Joshua Rigg. Chastened by either his conscience or his lack of expectations, Fred suddenly proposes to Mary. She sensibly declines, saying that Fred is not serious as yet and needs to demonstrate his goodwill. (Fred prevails upon poor Farebrother to plead his case to Mary, though Farebrother yearns for her himself!) At some point, Fred becomes a land agent and develops a professional attitude and demeanor.

Meanwhile, Bulstrode’s reputation for sobriety and piety is disrupted by the arrival of John Raffles, the stepfather of Rigg. Raffles comes to town bearing a scandalous story: Bulstrode cheated his widow’s daughter (from an earlier marriage) out of her inheritance. Embarrassed, Bulstrode offers money to Tertius or the hospital, but Tertius declines. Nonetheless, the disclosure of the offer embroils both Bulstrode and Tertius in suspicion, and they severally feel compelled to leave a town that has become too small for either of them.

Tertius is a tragic figure, sort of. His core fault is that he regarded a wife as simply someone who would relieve him of his workday cares when he returns home after a tough day at the hospital—someone who would be purely a bundle of unintelligent joy. (He had been jilted by a French Provençal lover, after which he seems to have abandoned the idea of romantic love.) He thinks Rosamond is the key to this idyll and is dazzled by her. Instead, she drags him down to her level. They overspend and Rosamond refuses to economize. (T. S. Eliot confessed he was frightened more by Rosamond Vincy than by Goneril or Regan in King Lear; worse than other dramatic or literary villains, she is a succubus with the power and desire to sap the energy and career of a principled and gifted man.)

Eventually, each of the marriages turns out as one might expect in a George Eliot novel. Tertius and Rosamond move to London, where he takes a job that makes more money but brings him little joy. He dies at the age of fifty, and Rosamond smartly proceeds to marry a wealthy old-school physician. Fred and Mary eventually marry, and live in Middlemarch apparently within their means and by all accounts contentedly.

Casaubon’s will directed that Dorothea be disinherited if she were to wed Will Ladislaw. She wrestles with the decision for some time, but eventually marries Will and disclaims the bequest. It turns out Ladislaw is the son of the widow’s daughter whom Bulstrode disinherited! (English novels are so tidy in tying up loose ends.) Will is engaged in public reform movements similar to the 1832 Reform Bill. (By the way, all the opening setup about politics (remember?) goes for naught, as Arthur Brooke’s Parliamentary campaign is unsuccessful.) Dorothea and Will have a daughter, and a son who is to inherit the Brooke estate. Even Farebrother finally gets something in the end, when Dorothea secures for him a sinecure in a parish church.

Far from her girlhood dreams of helping to comprehend all of mythology and faith, Dorothea is supposedly content within the confines of her domestic life as a wife and mother. But is George Eliot being serious or again sardonic? Judge for yourself:

Her finely touched spirit had still its fine issues, though they were not widely visible. Her full nature, like that river of which Cyrus broke the strength, spent itself in channels which had no great name on the earth. But the effect of her being on those around her was incalculably diffusive: for the growing good of the world is partly dependent on unhistoric acts; and that things are not so ill with you and me as they might have been, is half owing to the number who lived faithfully a hidden life, and rest in unvisited tombs.

My long-ago law professor Anthony Kronman, as part of his fascinating tour through what he calls neo-paganism, perceives that each character in Middlemarch has some redeeming virtues; none, not even Bulstrode or Casaubon, is a cardboard scoundrel. George Eliot exhibits admirable empathy in painting her tableau with such compassion and nuance. (Perhaps her lifelong interest as novelist and translator in reactions to rigid doctrine and dogma contributed to her stance.) This and other insights on belief in literature and art are found in Chapters 34 and 35 of Tony’s magisterial, nearly cube-shaped book Confessions of a Born-Again Pagan. These two chapters somehow remind me of Chapters 15 and 16 of the actually cube-shaped Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, in which Edward Gibbon gives his take on the reasons for the success of another creed—Christianity in ancient Rome (as he over-concludes, “I have described the triumph of barbarism and religion”).

Middlemarch stands the test of time. Virginia Woolf memorably called it “the magnificent book that, with all its imperfections, is one of the few English novels written for grown-up people.” George Eliot’s own biography seems equally remarkable for her determination to chart her own path. Her life and work juxtapose Victorian mores, universal human frailties, and ultimately and, somewhat surprisingly, the amalgam of mental states that each of us calls our faith.